SPECIAL REPORT… PLATEAU: Chilling story of deaths from snakes, reign of ‘native doctors’ as Nigeria abandons its own

Decades after Nigeria launched a team to look into how the country can produce antidotes to snake bites, and after late Prof Akunyili concluded a research on the same issue, nothing concrete has been achieved, and many poor farmers die yearly from snake bites due to scarcity of vials, and their high prices.

Orji Sunday was in Plateau State which has a high record of deaths from snake bites, and brings a situation report.

Hashimu Kaura’s face is flushed with a glint of inward grief.

His red eyes stare at the bed, catching the frame of a woman stretched across the mattress – groaning. There was no life in the bed. Only a flicker of morning sunlight – coming through the window louvers – and settling on the dull bedsheet.

The groan drew-out the inward sorrow Kaura was taming. His hands – placed on his knee – are jittery, shaking. Every now and then, he would feel the neck of the woman, pressing softly on her parched skin. And quickly replacing his palms on his own neck to know if it was hot, if she was running a temperature.

Late last year, he had concluded plans for the coming year; after working all year and having – in return – good harvest of yam, millet, beans, and benny seed. Not that all he had was much, but residual poverty has yielded shaky security in scarcity.

Silos and barns were made for a harvest of millet and yams. This was a hurt-like structure, capped with dry thatches, a small opening and a clay wall. So he set off to farm, December 31, 2018, with his wife Ibrahim Hauwa, for the husking of their millet. The sun, he recalls, was bright, no omen was insight.

Kaura and his wife had picked different spots on the farm. He was at the edge, cutting some new starks. His wife, bare footed – like most other farmers in the village – was moving through the field, gathering the millet into bunches – laying them on a tarpaulin for husking.

Most farmers don’t use protective equipment, making them vulnerable to attacks from snakes in their farms

Then she was struck in a particular heap. He drew forward to her cry, dragging his machete. When he was near enough, he lowered his sight to the pool of blood whose source was the open wound around her ankle.

He had been through this road before – its woes familiar. He searched quickly, the carpet viper that had bitten his wife had recoiled into the stark. He killed the viper, gathered its flesh into the basin. He needs it to show the doctors at the hospital. The doctors need it to know the right anti-venom to apply to his wife.

Now they are home, the blood continues to leak – a sign that is often connected to bites from carpet vipers. These bites, experts say, destroys the red blood cell and disrupts blood clothing, collapses the blood circulatory system, causing huge internal and external bleeding. From tending to his neigbours, who have suffered bites several times, he knew the signs, witnessed its fatality.

In reality, the mechanism of snake venoms is quite complex. Studies have shown that a single bite from the carpet viper or puff adder can contain over a hundred different toxins, which create varieties of effects subject to the quantity of venom injected, and time of presentation to the hospital.

“I did not have money to take her to the hospital. The doctors would ask for a deposit before treatment – without which they would abandon her,” he said, in nostalgia.

Even at that, he would try, the doctors might understand.

He would tell the doctors that Hauwa was the center of his life, barely two-years into their marriage. That Hauwa, 22, is the mother Zarah – his one-year-old daughter. That she was the last good memory left in him, helping kindle the spark of joy in his “broken life.”

“I felt that at least one person would understand how it feels to lose a new wife. A young mother.”

Experts estimate that in Nigeria, there is 174 bites/100,000 of the population – that’s is one in every five cases in Africa. Carpet vipers are responsible for 90% of bites and 60% of deaths. Bites are predominant in fertile rural communities, mainly affecting young people and children, during planting and harvesting periods.

Doma, is a one-hour drive on a motorcycle from Ajimaza – Kashamu’s hilly village. At Doma, he mentioned his woes to the doctors at Dalhatu Teaching Hospital, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. The doctor did listen to his story but like most hospitals in Nigeria, they can’t bypass the unbreakable ‘pay before service policy’.

“They told me to deposit 250,000 for five doses of the anti-snake venom. She would die if nothing is done immediately.”

West African Carpet vipers, regarded as the most dangerous snake in the world, are responsible for 90% of bites and 60% of deaths

There is this disarming normality in the way Kaura was telling his sad story. The kind of negative normality that comes from a rich reservoir of repeated calamity.

By his home, there was a grave to aid nostalgia. Many other families in his village had two or so graves too – fresh and old sometimes. The snake sorrow was evenly distributed, he says. And that lightened the burden of his misfortune.

“It is difficult to find a family that had not buried one or two persons because of snake bite. The deaths are numerous,” he said.

The World Health Organisation, WHO, estimates that 5.4 million people are bitten each year with up to 2.7 million envenomed, resulting in 81,000 to 138,000 people dying each year.

Kaura says he does not know if the “white man’s figures” included all his villagers that died, or his neighbours buried in the past months. But he was certain that since he was born 36 years ago, no one – from the government – white or black – had bothered to know the people who had died.

WHO says “the exact number of snake bites is unknown” because many of these deaths go unreported and available statistical researches are inadequate, especially in developing countries. Snake bites, it adds, is a “neglected public health issue in many tropical and subtropical countries.”

Still at Doma, Kaura scanned everything he has in his mind’s eye and their financial return at the point of auctioning them. His biggest bet is his motorcycle which might fetch 100,000 Naira. Then their yearly harvest: millet, benny seed, rice, yam – sold at that time, might give him another 100,000. But how would he raise the other 50,000? He might talk to a kinsman to give him a loan.

When Kaura left the hospital, he was certain he would run into trouble. First, it was rare to find anyone in his poor village who would have all this money to buy or even offer loans – half or full. He would have to move his lamentation from household to household to get bits of loan and his goods across different markets to find buyers.

But things went well, so that by twilight, he had gone back to the hospital to pay for the commencement of the treatment.

The deterioration on Hauwa’s left leg was rapid: blood and water has continued to flow, her eyes sleepy, with her flesh suffering a significant heaviness. It was strange, not surprising, because some victims at Dalhatu had worst fate and tinier chances of surviving.

Single bite from carpet viper or puff adder can contain over hundred different toxins that can damage tissues and cells in the body

Yet, when, as it happens, someone dies, his panic would find vibe.

In many villages, cultural and spiritual belief further complicate the snake stories. People believe that snake bites are shrouded in mysticism and witchcraft. They believe that offering material atonement to the gods would solve the problem. Or even some ‘forgiveness seeking submission’ to the individuals who projected the snake.

Over the years, the belief has waned; falling to the illumination of spreading Christianity.

All that might matter, but not to Kaura, not now that his beloved was inches away from death. For now, he was focused on watching the progress of the treatment. It was on the third day he realised his wife was closer to death now than she was when they walked into the hospital three nights before.

The third night, Kaura met the doctors to explain his observations, and later his fears. The doctor told him to seek a way forward and suggested transferring his wife to JUTH Comprehensive Health Center, Plateau State, Nigeria.

Zamko – an outpost of Jos University Teaching Hopsital, JUTH is one of Nigeria’s major specialist centre for treating snake bites. The other being Kaltungo General Hospital, Gombe State.

To move is money – which he lacks. To stay is death – which he abhors.

“All the money I raised finished in that hospital. But one doctor gave me 10,000 that night to move her to Zamko the next day,” he said.

January 4, 2019, they left for Zamko, it was a five-hour drive. Its black gate, and wide interior mingled with the washy yellow of its walls, and fairly old facilities, they were received by Dr. Titus Dajel, the medical superintendent of JUTH Comprehensive Health Center, Plateau State, Nigeria.

Dajel is a fleshy dark fellow, with a bulgy eye and broad nose.

Four years ago Dajel was posted to Zamko for a three-month short medical service. His experiences in the months to follow – the numerous deaths, the poverty and the hunger – made it an easy choice to stay back when the opportunity came.

The Federal government last support, which is the supply of 100 free anti-snake venom vials, to a hospital that treats over 2000 cases yearly, came last in 2015. At state and regional level, there have been recent interventions in Gombe state and north eastern states by the government. But this was a national crisis buried in silence.

“Hers is a critical case, so we had to take her in because delay could be too costly,” he said, referring to Hauwa. Dajel explains that the spreading injury could be signs of necrosis – a word so big, and alien to Kaura.

Necrosis is a premature death of the cells or tissue in an organ due to contact with toxics such as venom. But that is just one, not all the signs of snake envenoming. For instance, snake bite patients – depending of the type of snake and the quantity of venom injected – can experience excess bleeding, difficulty in breathing, and organ failure.

But time is central to it all. Dr. Nick Casewell of Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine says time of presentation could be the difference between those who survive, die or deteriorate.

“The longer it takes to get the anti-venom treatment, the worse the outcome. After about 12 hours, the patient has really missed a good opportunity where an anti-venom can have a good effect,” he said.

Kaura has heard this from the doctors in the past. But he says it is one thing to know the right thing and another thing to have what it takes to do it.

“Most times, you have to go around begging money first, it might take days to have something to bring for treatment. Before most families can raise this mighty money, the victims would have died or the condition would become too complicated,” Kaura said.

Dr. Dajel, the medical superintendent of JUTH Comprehensive Health Center, Zamko, had stepped into the ward now. He was moving from bed to bed, speaking in low tones, using local language. It was as if he was spreading short-lived smiles on those stoic faces lying defeated.

There is a new rising hope in Kaura’s eyes when the doctor neared Hauwa’s bed – but this too, like everything else about him – is fast and fading. Looking back, that feeling of optimism has fizzled out; displaced by a distant despair, far deeper than the present pain. His words were a stream of bitterness when – on that hot Monday noon – we sat to a long gloomy narrative.

Brother, I am sorry!

Kaura’s fall as a man started in 2015, when his brother Kaura Yahaya died. Yahaya was young – probably 24 – full of energy and obedient, Kaura recalls, his voice stuttering, and his eyes welling with tears.

He had guided his path as they grew – sharing everything with him, including a routine farm labour, home gist and future aspirations. “He would stand for me always. Whenever I was leaving home, I knew there is someone who can take care of all I am leaving behind,” he says.

One evening, Kaura and Yahaya sat to a gist, after a long day in the farm. It was blurry – the sun had slipped into the sky, but darkness was not in full control of the night. Yahaya stepped out to ease himself. A narrow alley that led to a nearby bush led him into an ambush: he stepped on a carpet viper and in a flash, its fang was deep into his flesh.

He did not scream like Kaura, he returned and sat silently to their talk.

“He said brother, I am dead. I did not understand what he meant. But when I looked at his leg and discovered the blood and the bite, I understood what he meant,” Kaura says.

That night, they left for Doma, to seek help in a local specialist hospital. But there was nothing but the transport to go with. At the hospital, the doctors looked at the situation and told him to deposit some money before they get off with medication. The total bill was over 200,000 Naira.

“That day, the total savings we had put together was less than 10,000. But I begged the doctors to commence treatment, but they refused. I left him at the hospital with a friend and went home to sell what we have and borrow from people.”

Kaura sold all their harvest for that year in two days but the income was way less than the bill. He started talking to friends around the community and nearby villages. After three days, he raised the money and rushed back to the hospital.

“When I saw him the third day, he was no longer black. He was red. He was swollen. I knew he would die.”

Resignation must have trumped optimism but Kaura gave his brother a chance to at least fight.

He paid the doctors. After several doses, Yahaya’s awkward breathing was finding some stability. But the bite occurred three days back, a lot of complications had set in and it was a matter of hours before Kaura would hear the reviving, or ravaging news.

But snake bites don’t always lead to death. But that’s not an outright goodness, says Dr. Casewell. This is because, most times, snake bite venoms can cause paralysis that may prevent breathing, bleeding disorders that can lead to a fatal haemorrhage, irreversible kidney and tissue failure – all prelude to life changing disabilities or even amputation.

“We talk a lot about people who did not survive snake bites,” he says. “But often we forget about people who survive and suffer from long-term morbidity. The snakes can cause horrific damages around the body part where the snake bite occurred.”

Kaura has an audience for his story in Zamko. He also has family and friends – all bounded by a thread of penury, death and snake nemesis.

Hospitals packed with victims

Yearly, JUTH Comprehensive Health Ccenter treats more than 2000 snake bite victims

The female ward is up with mothers – single and pregnant. The male ward filled with men – largely 25 – 30. The children ward flushed with children – quiet and tortured, except for outspoken Humphery Kyenbang. They were about 40 on admission here this week.

Kyenbang of Zamko is eleven. Her message is matured. She wants to be a doctor so she can fight the deaths. She says she has lost friends to the bites – people she shared the childish doctor dreams with. “I don’t also want to die,” she says. The rest of the kids admired her in some unspoken way. She was the only child that can speak English fluently here and others agree that she said their mind, though they did not understand what she said.

Back to the female ward, Kaura’s wife is losing her breath. It seems this will be a slow death but Kaura’s hopes remain firm. He had paused his story now, focusing on Hauwa who is struggling to change her sleeping position. He held her, lifting the dead leg, and placing it in its place. He allowed some absorbing silence brew.

“By 5 pm that day, my brother whispered an apology for all I had been through and started crying. Then he died. Since that day, I have never been myself. My life has never been the same after that day,” he said.

The Snake Grave

Graveyard now home to many snake bite victims

We drove five minutes away from the hospital now, to Gunnung, in Langtang, Plateau state, Nigeria. A narrow path that curves leftward led us further into a dusty plain. The plain had huts, and sparsely standing boabab trees. The huts had thatches. The thatches were dry, weaved together and old. Dr. Dajel led the way. I was behind.

The day before, Joshua Emmanuel, 28, had killed a carpet viper in his farm at Gunnung, stamping it out of a narrow burrow with a machete, cutting it into bits, before stretching its mutilated body in display of vengeance.

But a carpet viper had killed his father first. That was two decades ago, when he was eight years old. He had killed nearly more than 15 vipers this past planting and harvesting season, he has no whiff of triumph because when the viper killed his father, it took a better part of him.

But Casewell says eliminating the snakes is not a decent option, as snakes actually make a far less hostile neigbours in the eco-system with a better management of the problem.

“The snakes even help rural farmers by keeping rodents and pests in check. If the snakes are limited, rural farmers would lose a lot. The farmers need help to share the eco-system safely with the snakes.”

Else, snakes add fearful fascination to nature. The black neck spitting cobra, for instance, is a thriller to watch in safety. The swift movement of its dancing tongue, the spreading of the hoods, the twisting and spitting. The carpet viper – scratching its scales by ruffling its bodies and rolling in semi-circles give a sizzling warning sign.

There is a grey grave yard at Gunning, homed by the bodies of snake victims. Even in death, the poor are separated from the rich. At Gunnung burial ground, there are three graves marked out by their mounded cement backfill, headstone and scribbled dates. The other far more common graves are marked with three stones, dropped apart in measured distance.

One of the instigators which has brought death to many poor farmers

“Life after my father has never been the same,” Emmanuel said. But the greater task, however, was now to survive the vipers not to immortalize the nostalgia of his father’s death.

Choosing the Cheaper Death

Emmanuel was eight when his father died. With the eye of a child he recollects hazy details about his father’s death. He remembers the day his father returned from the farm with an unfamiliar solitude after the bite. They moved him to a herbal priest for traditional care.

By the second day, his father died.

The herbal doctor who nurtured him in those last days said it was the will of the gods. But, 56-year-old patient, Tali Nansel, says those kind of deaths have far greater connection to poverty than divinity.

“It is not enough to preach that people should avoid herbal care. How can you afford the huge bill in the hospital when it takes so much struggle to eat once in a day? People would rather go for the cheaper death,” he says.

Nansel suggest that more than 90 percent of the people in his village are included in the 87 million people living in extreme poverty that helped Nigeria overtake India as the world capital of poverty according to a recent report from US-based nonprofit public policy organization, Brookings Institution.

Nankpak Vonga – Zamko’s famous herbal snake healer says it is the potency of his herbs that drive his fame as well as the affordability of his treatment. He charges as low as 5,000 Naira for treatment – which is less than five percent of what it takes to averagely treat a snake bite in the hospital. Vonga is tall and happy, powerful in his own eyes.

Herbal healer, Vonga of Zamko, Plateau, Nigeria administers herb to a patient

Last year, he had close to hundred patients from eight states. Vonga does not run diagnoses but he has his own-self trusted traditional expertise. This expertise, he says, fails sometimes when it is the will of the gods, or the attitude of the patients like late presentation defiles medicament.

“I can tell the quantity of venom deposited in a person’s body by the way they cry when they receive the herbs,” he says. “if the person stops crying, it means the herbs have taken away the toxins in their body.”

Govt joins fight to tackle menace

He started making his search for the perfect herb in the early 1990s; around the same period Nigeria’s Ministry of Health showed definitive interest in tackling snake bite menace. The year was 1991.

The Ministry of Health, under late Professor Olukoye Ramsome Kuti, assembled a study group – Echitab Study Group – involving partners from Liverpool School of Tropical Studies, Oxford University, Ministry of Health of Nigeria and Instituto Clodomiro Picado with the aim of producing anti-venom that would be effective against Nigeria’s most common venomous snakes: carpet viper, puff adder, and black neck spitting cobra.

The group succeeded, but after losing government funding, it metamorphosed into a not-for-profit organisation in 2009. It serves as a local subsidiary of the Instituto Clodomiro Picado (ICP), University of Costa Rica that – in collaboration with EchiTAb study group Nigeria/UK and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and University of Oxford- produces the EchiTAb Plus, which is effective against the puff adder and black neck spitting cobra.

On the other hand, ESG, keeps link with Micropharm Ltd, UK and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene for the production of EchiTAb G, effective against the Nigerian carpet viper – simply regarded as the most dangerous snake in the world. Its anti-snake venom selling for less than $75, depending on exchange rate, has been used for the treatment of 18,500 treatments, with an estimated supply of over 37,000 vials of anti-venom.

Africa needs, annually, 1.6 million vials, Nigeria alone needs 245,000 vials but the continent gets less than 100,000 vials before 1994, a report from the EchiTAb Study Group, shows. In Nigeria, 12 States are at risk.

The domestication of anti-snake venom, observes Nandul Durfa, the medical director of the EchiTAbstudy group Nigeria/UK, would have solved a lot of problems. The UK company – MicroPharmaceuticals Ltd – said it would cost Nigeria eight million dollars to domesticate the production of anti-snake venon, transfer the expertise to locals and drive down the cost to as low as 5000 Naira.

The government did not fund it.

Why?

“It is a poor man’s disease. Those effected are nobody. But when snake bites the president, or the governor, the government would take a strong action to stop this. Ten percent of the Ebola intervention fund could have saved many poor lives in the bush” says Dr Dajel of the Comprehensive Health Centre, Zamko, Plateau state, Nigeria.

Driving back to Zamko, the hillocks mingle with small rocky formations and slopes and valleys. Its plains are fused with pink petals of blossoming cardiflowers and short green shrubs squeezed between rocks. The snakes also use the rocks – usually near homes – as habitat, intensifying hostilities between them and the communities.

Hauwa is awake now, her eyes are small and seductive. Kaura had whispered something to her ear, but her patched lips struggled to part as she made a failed attempt to smile. Dajel looked at the open wound, wobbled something like a white wool on it.

“She is improving,” he says. “The case is complicated but she might likely live.”

It would seem nothing concrete has been done by the Nigerian government to ameliorate the plight of these rural dwellers, who have been dying by the hundreds on their farms and homes as a result of shortage of anti snake venom drugs in the country, which studies show can be produced locally, and the price reduced drastically.

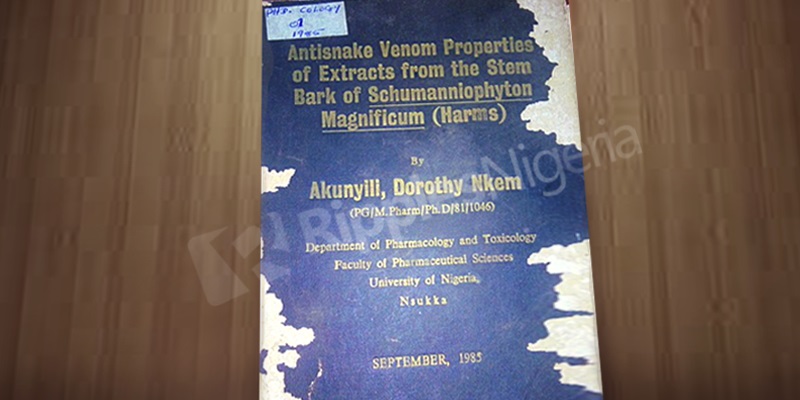

This is happening despite a research conducted 34 years ago by Professor Dora Akunyili in 1985 which showed that Nigeria can produce the anti snake venoms locally using extracts from the stem bark of schumanniophyton magnificum, a plant found in abundance in many parts of the country.

Prof Akunyili’s research work

Unfortunately, her research findings, like many of such endeavors in the country have been left to accumulate dust on book shelves of government institutions across the country, while the citizens die.