INVESTIGATION…How endless oil spills leave Niger Delta severely polluted, livelihoods ruined and citizens poisoned

A six-month long investigative story, with laboratory tests, by RUTH OLUROUNBI and KELECHUKWU IRUOMA reveals how contaminants in the air, water and soil, as a result of the oil spills in Nigeria’s Ogoniland are affecting the health of people and how the slow cleanup exercise is putting more people at risk of dying.

Eric Dooh, 60, had just returned from Goi, a community in Ogoniland, within Nigeria’s Niger Delta region. He had visited his family’s property in the community he left a few years back due to air pollution. Near the property is a large river where men fish, but it has been contaminated as a result of oil spills, causing unending pollution that pervades the air.

He was exhausted. He sat on a red couch in his sitting room wearing a red traditional shirt and cap. His eyes were red like fire due to the poor quality of air containing harmful gases such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide he was exposed to.

Dooh had hung a plain trouser he wore to the community the previous day on a wall. He stood up, went to the place the trouser was hung and dipped his right hand inside one of the pockets. He searched for a sachet of franol — a medication that relieves breathing difficulties — he usually took after returning from the oil spill site but could not find it. Goi is one of the affected communities ravaged by oil spills.

Chief Eric Doo sits on a couch in his sitting room in Bodo. Photo by Ile Umoru

“Our people suffer very seriously; they inhale chemicals,” lamented Dooh. “My mother and father died in 2005 and 2012 respectively. They were diagnosed with respiratory disease and could not survive it.”

Nigeria has the largest oil-producing mines in Africa with the bulk of its crude laying beneath farmlands and rivers in Ogoniland with oil companies like Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) extracting about 100 million barrels of crude every year.

Crude oil is very important to Nigeria’s economy. The Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS) revealed that crude oil export accounted for N3.74 trillion or 70.84% of total exports in the third quarter of 2019, making it the most exported product in Nigeria while its contribution to the Gross Domestic Products (GDP) was 9.77%. Despite this, the oil-producing communities suffer from numerous oil spills.

Between 2003 and 2014, there were devastating oil spills from the Bomu manifold, a Shell facility at Kegbara Dere (K-Dere) located in Gokana local government area of Rivers State. Shell has been pumping oil from the Niger Delta since 1958 and it remains the largest multinational oil company operating there.

Although Shell has not pumped oil from its oil wells in Ogoni since 1993 when Ogoni activists led protests against the oil company for destroying the environment, halting its operations, its pipelines still carry crude oil worth 150,000 barrels daily through the region to its export terminal at Bonny Island on the coast.

The pipelines were reported to be ageing and poorly maintained, prompting multiple splits as a result of internal pressure, spilling thousands of barrels of crude oil. Amnesty International, a human rights organization, in its 2015 report said about 352,000 barrels of crude were spilled between 2007 to 2014.

But the major oil spill occured in 2009 when fire from the Bomu manifold burned for 36 hours and spread to neighbouring Goi and Mogho communities, causing damages that destroyed the people’s livelihoods.

Contaminated River at Bodo community. Photo by Ile Umoru

Loss of livelihood

That cold night, 35-year-old Dorgbaa Bariooma kissed her children and husband good night, turned off the light switch and went to sleep. Neither she nor thousands of people at K-Dere knew the event would change their lives forever. The first thing she woke up to was the heat from the explosion.

“It was as if our house had been set on fire. Later came the smell of crude oil. It was so bad we could not breathe well for the first few months,” said Bariooma.

The oil spills had devastating impacts on the forests and fisheries that the people depend on for their food and livelihoods. Many K-Dere residents grew up near Kidaro Creek, where they fish. Fishing was one trade they excelled in but the harvest is poor as the creek is now contaminated with crude oil.

“Growing up, I would watch my father fish from this very creek and on sunny days like this, many of us will come to the creek to cool off. Here, there was once luscious vegetation and the sound of laughter and happiness was infectious,” said Erabanabari Kobah, an environmental scientist from K-Dere as he pointed towards the oil on the creek.

Oil spill contaminated Barabeedom swamp in K-Dere community

Reaching the intersection leading to Goi, the smell of crude oil pervaded the air and deserted houses were seen around the community. As the car conveying the journalists screeched to a halt and its windows wound down a kilometer from the spill site, everyone covered their nose as the smell of benzene spreading through the air intensified.

Mounted near the riverbank which thousands of people depended on for food was a public notice inscribed “Prohibition! contaminated area. Keep off.” The river has been contaminated with crude oil crawling on the water. Fishermen could no longer catch healthy fish but a few unhealthy crabs.

Displayed public notice stopping people from performing activities at Goi community. Photo by Ile Umoru

Raphael Vaneba, 47, still goes to the river to fish despite the environmental and health risks involved. He came out of the river carrying a fishing net on his right hand and an open gallon containing five crabs he had caught. His body was soaked in crude oil. Soon he dropped the fishing net and started to itch every part of his body.

“I scratch my body whenever I come out of the contaminated river after fishing. We do not catch fish here anymore because the spilled crude oil has killed them and we don’t get money,” he lamented as he opened the mouth of a crab to show crude oil inside.

Caroline Gbogbara sells food items at the community market in Bodo, one of the affected communities that experienced major oil spills in 2008 and 2009. She goes to the river to pick periwinkles to sell but since the oil spill happened, she was not able to pick periwinkles. As a farmer also, her farmlands were affected by the oil spill but she still farms on the contaminated farms. When it’s time to harvest her cassava and vegetables, she smells the stench of crude oil.

The reporters and a fisherman soaked in crude oil who had returned from the contaminated river in Goi. Photo by Ile Umoru

“We don’t have anything to eat. Farmers farm on lands filled with crude and have no choice but to eat the contaminated produce. Families are forced to eat the chemicals from the spills,” she said.

According to the Center for Environment, Human Rights and Development (CEHRD), oil spills could lead to a 60% reduction in household food security and is capable of reducing the ascorbic acid content of vegetables by as much as 36% and the crude protein content of cassava by 40%, which could result in a 24% increase in the prevalence of childhood malnutrition.

Besides the contamination of rivers and farmlands, the communities’ sources of drinking water, which are mainly underground water and streams, have also been contaminated. Goi has a stream where the people collect water to drink. The stream which pathway is now bushy no longer receives visitors to fetch and drink from.

Contaminated stream where people go to fetch drinking water at Goi. Photo by Ile Umoru

“If you fetch the water and pour in a glass cup, you will see crude oil inside. We are drinking poison here,” lamented Dooh.

Exposure to toxic substances

Petroleum hydrocarbons can enter the body through the air, food, and water, or when one accidentally eats or touches soil or sediment that is contaminated with oil. Crude oil contains a significant amount of aromatic compounds including Benzene, Ethylbenzene, Toluene, and Xylenes (BTEX), which are the most dangerous gaseous elements of crude oil and poses the risk of acute or chronic toxicity in humans during its production, distribution, and use.

In 2011, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) published a report on the impact of the oil spill on the communities in Ogoniland after the federal government hired its services to assess the extent of the oil spills.

The report revealed an appalling level of pollution, including the contamination of agricultural land and fisheries, drinking water, and the exposure of hundreds of thousands of people to serious health risks.

It revealed drinking water from wells in communities in Ogoniland was contaminated with benzene, a known carcinogen at levels over 900 times above the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline.

Before oil was discovered in Bodo community, Emma Pii, chairman council of village heads, said the people were living a peaceful life and the economy was buoyant. But with the discovery of oil, they started living in bondage.

Fishermen inside the contaminated river at Goi. Photo by Ile Umoru

“Instead of oil to be a blessing, it became a curse to us,” said Pii. “What Shell has done is to take our oil and make money from it while the people who own the oil are suffering.”

It’s a terrible moment for the people of Ogoni who now live with the consequences of mistakes that were not their doing.

Eleven years after the major oil spills that rocked the oil-producing communities, their health is now failing them. They complain of symptoms, of which they do not know the underlying cause.

Oil spills release certain harmful chemicals such as benzene and toluene. Benzene is a known carcinogen while toluene can cause kidney and liver damage. Many spills also cause fires, which release toxic fumes that can cause respiratory problems.

Blood Tests

Each year, hundreds of post-impact assessment studies are conducted to assess the impact of the hazards generated by the oil industry on the social environment and human health due to oil spills. The reporters decided to do blood testing to determine how oil spills impact the health of the people of Ogoni.

Blood samples taken for laboratory investigation on the effect of oil spill in Ogoni. Photo by Ile Umoru

The reporters consulted Dr. Olawale Shipeolu, a medical doctor in Port Harcourt who recommended we carry out blood tests to check the kidney and liver functions of the people.

Chukwunonso Okoye, a clinical lab scientist with the Union Diagnostics and Clinical Services, traveled with the reporters to Ogoniland to take blood samples of 50 non-smoking and non-drinking volunteers from Bodo, Goi, K-Dere, and Mogho communities. The collected samples were then taken to the lab’s headquarters in Lagos for analyses.

Full Blood Count (FBC), electrotype urea and creatinine (e/u/cr) and Liver Function Test (LFT) were conducted on 50 blood samples drawn from 26 males and 24 females, including youths and adults.

Based on the results generated by the Union diagnostics and clinical service, no electrolytes were deranged, indicating nothing was happening with the kidneys. However, the results showed some level of derangements of liver enzymes.

The laboratory scientist drawing a blood sample for investigation. Photo by Ile Umoru

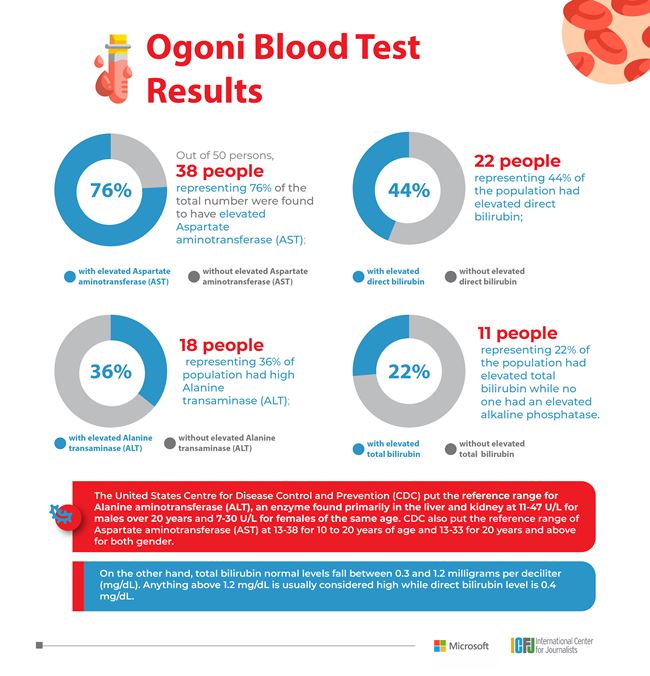

Out of 50 people sampled, 38 people representing 76% of the total number were found to have elevated Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and 18 people representing 36% of the population had elevated Alanine transaminase (ALT).

The United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2008 put the reference range for Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), an enzyme found primarily in the liver and kidney at 11-47 U/L for males over 20 years and 7-30 U/L for females of the same age.

CDC in 2012 also put the reference range of Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 13-38 U/L for 10 to 20 years of age and 13-33 U/L for 20 years and above for both genders.

Based on the results, more than half of the volunteers had their unit levels higher than the CDC reference range.

The laboratory scientist drawing blood samples from the people of Goi. Photo by Ile Umoru

With their consent, Stephen Kpea had an elevated AST of 253 U/L and ALT of 107 U/L while Clement Glogo had an elevated AST level of 164 U/L.

Young people within the age of 18 – 25 also had elevated liver enzymes. 19-year-old Gbogbara Barriduula had an elevated AST of 60 U/L while 20-year-old Happiness Sunday had an elevated AST of 62 U/L and ALT of 79 U/L.

On the other hand, results for direct bilirubin showed that 22 people representing 44% had elevated direct bilirubin; 11 people representing 22% of the population had elevated total bilirubin while none had an elevated alkaline phosphatase.

According to the Union Diagnostics, total bilirubin normal levels fall between 0.3 and 1.2 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). Anything above 1.2 mg/dL is usually considered high while direct bilirubin level is less than 0.4 mg/dl.

For example, Lucky Yira’s total bilirubin and direct bilirubin were 8.0 mg/dl and 3.9 mg/dl respectively.

“Such elevated liver enzymes may indicate damage to the liver cells and such patients might be prone to liver disease,” said Dr. Festus Davies of the Sapphire Health Group.

The test results showing the effect of the oil spills in the liver cells. Credit: Olaseun Oladosu

A study published in the Journal of Hepatology by Dr. Kezhong Zhang of the Wayne State University School of Medicine’s Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics and his team discovered that exposure to airborne particulate matter in fine ranges (PM 2.5) has a direct adverse health effect on the liver and causes hepatic fibrosis, an illness associated with metabolic disease and liver cancer.

Also, research by Kesava Reddy and Mark D’Andrea of the University Cancer and Diagnostic Centers, Houston, Texas, linked elevated AST and ALT to exposure to toxic substances due to oil spills.

“That is the effect of the environment,” said Dooh, when he learnt he had an elevated AST.

“Any young man who wants to [continue to] stay here will definitely not see tomorrow.”

Migration looms

At 60, Dooh still remembers how his parents suffered and died due to diseases caused by the oil spills. Dooh’s anger was felt through his voice as he spoke.

Houses in Goi have been deserted as residents run for survival. While some migrated to Port Harcourt, others migrated to neighbouring communities.

Dooh now lives with his family in a small bungalow in Bodo having been asked to leave Goi by UNEP to protect themselves.

“We are migrating,” said Pii. “We are refugees because when the means of livelihood of the people have been destroyed and you do not have what to sustain you, you have to migrate to where you can do something to survive.”

89-year-old Tudor Tomii is from Goi community but now lives in Bodo due to the oil spills that ravaged his community.

The laboratory scientist drawing a blood sample from a sick woman in K-Dere. Photo by Ile Umoru

“Here I am living in diaspora because of oil pollution. We can’t eat anything we plant there. We order anything we eat from Port Harcourt. We buy water from outside Ogoniland. Normally we drink from streams. Since the stream is polluted, we don’t have anywhere to drink from,” he lamented.

Compensation to the communities

The people of Bodo have been compensated by Shell after they filed a case in the United Kingdom, where Shell is incorporated. Shell accepted the responsibility for the oil spills in Bodo. The parties settled in 2015 and US$83.4 million, 82 percent short of their original demand of US$454.9 million was paid to the people of Bodo.

Pii said every indigene of Bodo who was 18 years or above received N600,000. But they are still not satisfied because the oil spill is yet to be cleaned.

Goi, Mogho, and K-Dere are hoping to be compensated by Shell for destroying their livelihood. K-Dere had filed a case for compensation in a Federal High Court in Port Harcourt against Shell for the havoc caused on its land.

But Shell said it can only pay compensation to communities whose oil spills occurred as a result of operational failure and not spills caused by sabotage and vandalism.

“The majority of the spill recorded in the Niger Delta, including in Ogoniland were as a result of sabotage and vandalism,” said Shell’s spokesperson Bamildele Odugbesan.

“Every operational spill with impact is what we pay compensation for and if there is no impact, we don’t pay. Our pipelines have continued to suffer third party interference.”

A contaminated oil spill site at K-Dere community. Photo by Ile Umoru

Slow cleanup exercise

UNEP in 2011 said the environmental restoration of Ogoniland was possible but could take 25 to 30 years if a comprehensive clean up exercise could begin immediately. It recommended the creation of an Environmental Restoration Fund (ERF) for Ogoniland with a capital of USD 1billion, to be co-funded by the federal government, Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) and Shell for the remediation of polluted sites in Ogoniland and restoration of livelihoods of people in impacted communities.

A year later, the Nigerian government established the Hydrocarbon Pollution Restoration Project (HYPREP), an agency under the ministry of the environment with the mandate to implement the environmental clean-up programme in Ogoniland.

In 2016, the government then launched a USD 1 billion clean-up and restoration programme of the Ogoniland, with $200 million to be released every year. But the cleanup exercise did not kick off immediately.

UNEP said continued delay in the implementation of the recommendations will not only undermine the livelihoods of the Ogoni communities. But it will also cause the pollution footprint to expand, requiring a fresh investigation to rescope the place and determine the extent of the contamination. Ogoniland is a high rainfall area and the spill has been carried across farmlands and into creeks and the root zone to other areas.

The cleanup exercise later took off in 2019, eight years after UNEP’s recommendation. So far, the sum of $360 million has been released to HYPREP out of which less than $30 million has been spent.

But the cleanup exercise has been slow.

“The cleanup may not be successful,” said Kobah.

“The speed of the cleanup is so slow that the desired results will not be achieved. Since 2011, this place has remained contaminated. This is what the people have been living all through their lives with. This is suicide. The people have been crying and complaining.”

Crude oil moving on water at the river in Goi. Photo by Ile Umoru

HYPREP said it is only following due process to have a successful cleanup exercise. Being quick without observing the rules, according to HYPREP, will be the reverse side of the slowness bad coin and that will be counterproductive.

“The Ogoniland cleanup project is not slow, it is on course and going at a pace that standard remediation practice allows,” said HYPREP’s spokesperson Joseph Kpoobari Nafo.

Sam Kabari, an environmental expert and a lecturer at the Nigerian Maritime University, Delta State, disagrees. He sees the drag as a bureaucracy every government agency experiences in the procurement and civil service processes. He believes HYPREP will only achieve its mandate if it functions independently.

“We wanted an independent HYPREP that would own its processes and take critical decisions towards achieving its aims and mandates itself. HYPREP should be in charge of its funds, decisions and day-to-day running,” he suggested.

Dooh accused HYPREP of only cleaning less impacted sites, leaving the highly impacted areas. But HYPREP said the highly impacted sites are not being cleaned yet because they are complex sites, which will be difficult to clean by any of the Nigerian contractors.

According to HYPREP Project Coordinator Marvin Deekil, “We are coming to the highly impacted areas. We need more detailed and extensive work in delivering those sites. That is why we had further strategic meetings in Geneva with UNEP so that we can come up with a better way of addressing those sites. We need international contractors.”

Declare state of emergency in Ogoniland?

The people of Ogoni want the federal government to declare a state of emergency in the region to cleanup the entire affected areas.

“With what we have seen here, what we have passed through, what has happened to our children, the elderly and pregnant women, we want the government to declare a state of emergency in Ogoniland,” Pii said.

He said the emergency measures such as the construction of hospitals and providing alternative sources of water for the affected communities have not been done, putting the health of the people at risk.

Emma Pii, Chairman, Bodo Council of Village Heads at the spill site. Photo by Ile Umoru

Kabari, who is the Head of the environmental and conservation unit of CEHRD described UNEP’s inability to implement the emergency measures as unacceptable. He said the emergency measures were supposed to have been implemented before the actual remediation activities began.

“Stakeholders are yet to see the provision of portable drinking water in communities where the groundwater was significantly impacted. Stakeholders are, however, doubtful of HYPREP’s understanding of the UNEP report given the misplaced priority of sequence of the UNEP report implementation,” he said.

“Water for Ogoni is almost there,” said Deekil.

“This year [2020], we told you there will be water in the communities. That is the commitment the government is keeping and we are working very hard to ensure it happens. We are going to be seeing the [water] contractors in the communities very soon.”

To avoid future oil spills, Shell said it has taken effective steps. For the last seven years, Odegbesan said Shell has replaced 1,300 kilometers of its pipelines, including in Ogoniland.

“We also monitor the pipelines to ensure nothing is happening to them. If something is happening to them, we can respond swiftly. We have helicopters with high definition aerial cameras hovering over our assets daily to capture the illegal activity of our pipeline. We have intensified our campaign among the local people not to go near oil facilities and engage the public on the danger of pipeline vandalism”, he said.

Dooh is sad the cleanup exercise has not been effective as expected. He believes until the people are compensated and HYPREP follows UNEP recommendations as instructed, Ogoniland cannot be restored.

“If the cleanup becomes effective, people will go back to the communities and start living well,” said Dooh. But if the cleanup is not successful, Ogoni people will continue to suffer.”

This investigation was supported by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and Microsoft Modern Journalism.