INVESTIGATION: Kwara court facilities crumble under neglect; FOI Law non-existent

The enticing aroma of bean cakes, fondly known as Akara, filled the entrance of the building Afon community regards as the Court. The bean cake vendor, commonly called Iya Alakara, operates just outside the open structure, beside the tarred road—a popular spot for small food businesses like hers. Several goats lounged peacefully in the shade of the court building, creating a striking contrast between the bustling activity of food purchase and the quiet neglect of the court facility.

Although it was around 11 a.m., the building appeared deserted, devoid of people and signs of activity or development. Iya Alakara, as passersby know her, mentioned that court staff are usually contacted in advance to confirm their availability.

“If there’s a court case, please get their phone numbers and call them,” she emphatically advised after selling some bean cakes to this reporter.

The forefront of the courthouse

While waiting for the staff contacted, the Akara seller responded to questions regarding how poorly the judicial structure looked. “This building was constructed decades ago, and it has become shameful to the town because it is still referred to, and operational as the Court,” she said.

The Magistrate Court Project

Magistrate Courts of Law in Nigeria have jurisdiction over criminal and civil matters; six are existential in Kwara Central. In 2021, ₦10.9 million was budgeted to renovate the Magistrate court at Afon, the headquarters of the Asa local government area in Kwara’s central senatorial zone.

Udeme, a social accountability platform designed to hold the Nigerian government accountable for funds released for developmental projects displayed on its website the details of the court project. The court’s renovation has the Kwara State Ministry of Justice as the supervising ministry and the project, as at the time of this report, is also confirmed to be unexecuted by the Udeme project tracker board.

At first glance, on the initial visit, the building appeared to be in a state of disrepair in agreement with earlier findings.

During this reporter’s second visit on June 24, 2024, Mustapha Akinyemi, a court staff, opened the courtroom door and provided a tour of the interior. Iya Alakara, who refused to share her real name, had called for him.

The courtroom has long benches and a small ray of light sneaking in through wooden window frames. Beyond doubt, the furniture inside were decades old and in desperate need of replacement. Also, the courthouse is bereft of electricity, a toilet facility, and a proper office for the judicial staff.

Interior of the court

“Since this building has been constructed, no renovation has been made,” Mustapha told this reporter, with a gentle shadow of disdain in his eyes.

Touring the building with this reporter, he pointed in a direction and said, “This is the wooden door to the court office, I made it with my own money,” indicating that even janitorial staff take on the responsibility of repairing Law Courts.

“The curtains in the court office had been there before I was born,” said the middle-aged man before commenting that only the High Court is touched in the whole of the local government by the government and is in good shape.

Shockingly, he revealed that the earlier building is the Area court which is ‘borrowed’ by the Magistrate Court whenever they have court cases. This raised the question of the exact location of the Magistrate Court, which Mustapha was willing to share.

The Magistrate Court is about 400 meters from the Area Court which the staff led this reporter to. The Magistrate Court’s building was overgrown with bushes within and out. It was nothing short of a growing forest residing in a building. With no roof and damaged doors and windows, it was an eyesore, condemned to serving a long-term state of degradation.

Commenting on the issue, Sam Olorunfemi, a developmental expert said that the constant lamentation over the deplorable state of courtrooms is becoming overwhelming and disturbing to the overall effectiveness of the judicial system.

He mentioned that at the state and local government levels, courtrooms are usually faulted, which largely contributes to the delay in the dispensation of justice in Nigeria and makes the working environment very difficult for justices and legal practitioners.

“That is why we keep pushing for financial autonomy for the judiciary at the state government level: so that they have and spend money on critical projects without passing through the executive,” he stated.

Beyond Dilapidated Buildings, a National Law is Dilapidated in Kwara

In 2011, The Freedom of Information (FOI) Act was signed into law by the National Assembly. The primary purpose of the law is to enforce citizen’s access to public records and information, uplifting openness and good governance.

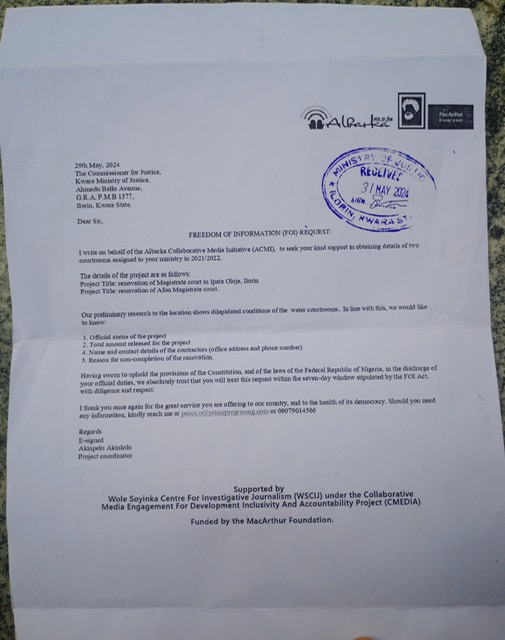

Empowered by this law, this reporter submitted a FOI request letter on May 31, 2024, seeking the details of the court-building project to the Commissioner of Justice’s office. The request specifically sought details on two Magistrate Court renovation projects in Afon and Ilorin. It asked for information on the amount paid, the contractors involved, and the reason(s) for the projects not being completed.

The acknowledged FOI request sent to the state ministry of Justice

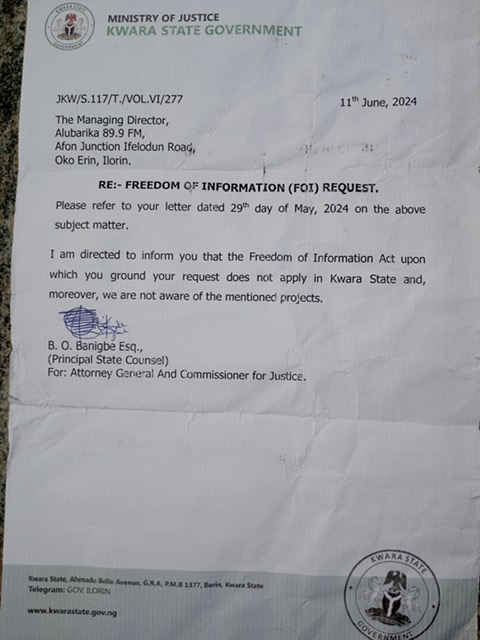

A call was made to this reporter on June 11, 2024, to come and receive the response to the FOI letter which she swiftly visited their office for. Contrary to expectations, the Kwara State Ministry of Justice failed to demonstrate the accountability that they were expected to embody. The response states that the FOI law does not apply in Kwara and that t ignorant of the mentioned projects opposing the information on Udeme.

With the development, this reporter requested to speak with a higher authority for clarifications, but the official in charge was absent. One of the secretaries eventually released the phone number of the Commissioner’s representative whose signature is on the letter.

Through a phone conversation, he was contacted. “The details you are asking for, are not within our disclosure. FOI has not been domesticated in Kwara state. The information I disclosed in the letter in response to your letter as authorized by my superior is all I have within my knowledge and that is what I have given,” were the exact words of B.O Banigbe Esq., who is the Principal State Counsel.

Response by the Kwara State Ministry of Justice to the FOI request

What do the Experts say?

In an interview with Lukman Raji, a legal practitioner and public accountability expert, he explained the reasons behind the non-enforcement of the FOI Law in Kwara State.

In his narration, towards the end of the tenure of a former governor, Abdulfatai Ahmed, a civil society organization (CSO) promoting good governance and transparency, through one of the honourable members of the state assembly introduced the bill for FOI Act to the house, in 2019.

Civil society bodies and media organizations were joyous when the bill was passed into law. Following the passage of the bill, the Former Speaker, Ali Ahmad, instructed the Clerk of the House to prepare a copy of the legislation for onward transmission to the governor for assent.

The neglected Magistrate Court in Asa LGA

Professor Abdullateef Alagbonsi, the founder of Elites Network for Sustainable Development (EnetSud), the CSO behind the bill, said that the narrative after the submission was ‘sadly’ disappointing.

Upon assessing the law, the current governor, Abdulrahman Abdulrasaq, made a few changes to fit the context of Kwara State. He requested two specific alterations: first, to extend the period allowed from 7 to 14 working days, unlike the federal law; and second, to increase the penalty for violators to include both two years of imprisonment and a ₦500,000 fine. The federal law stipulates either two years of imprisonment or a ₦100,000 fine.

While these changes initially seemed promising, it has been over five years since the bill was introduced and has been stagnated. This delay suggests that the Kwara government may not want the bill to become law.

“So to date, the bill has been unable to get the corrections in the state house assembly despite numerous bills they have passed within the last four years,” Lukman said, “In Fact, the bill is as good as dead because the house of assembly is not planning to touch it.”

Side view of the courthouse

The Speaker of the state’s House of Assembly, Honourable Yakubu Danladi Salihu and the Executive appear to not be bothered about the law despite reminders from the opposition party, media and CSOs. According to Lukman, the state has the power to implement FOI domestication because the law falls under the Concurrent Legislative List which allows both the federal and state governments to have the authority to legislate.

On the other hand, Moshood Ibrahim Esq., another legal practitioner, stated that the type of government practised in Nigeria, which is federalism, does not allow any state the right to reject national laws outrightly.

Indeed, he said, “States have their levels of government: Executive, Legislative, and Judiciary. So before a law can start working, they should domesticate it. But there is a Court of Appeal judgment.”

Moshood went on to reference the Court of Appeal case between ALO v. SPEAKER, ONDO STATE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY & ANOR, CITATION: (2018) LPELR-45143.

A certain Martins Alo requested the audited report of the Ondo State government between 2012 and 2014 to know how public funds were expended. However, the request was not responded to, which prompted his legal action seeking judicial redress.

In 2016, the ruling of the Akure Division of Ondo State High Court was that no individual had the legal right to the state’s expenditure documents. The court held that the FOI Act does not apply to states and that the request made was not even in the public interest.

But, a three-member panel of the Court of Appeal overruled the High Court’s decision. It aligned with the appellant, that FOI Law applies to every state in Nigeria and the request is for public good.

Therefore, “As a national law, there is no need for them to domesticate the FOI before they start working with it,” Moshood asserted.

Difficulty in Open Governance Space in Kwara

“This lack of implementation of the FOI in Kwara State has made it difficult for citizens, civil society organizations, and media organizations to access information about how public funds are spent in the state,” Prof. Abdullateef explained.

Speaking about EnetSud, he lamented bitterly about how the state has made public accountability and transparency extremely challenging and complicated. He pointed out that whenever a request is made, government agencies hide behind the excuse of non-implementation of the FOI to withhold information, and there is no legal backing or power to pressure them into responding.

“The government bodies only release the information they choose to release,” he said.

By Peace Oladipo

Editor’s note: The name of the court staff has been changed to protect the identity of the individual involved.

This story was produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation