INVESTIGATION: Benue communities, residents in pains as govt neglects PHCs

In many Benue State communities, women especially suffer from the absence and non availability of staff and medicine in the PHCs many of which have been abandoned and left to rot. MANASSEH MBACHII reports that child birth and survival is a harrowing experience for residents of these communities who continue to live with the pains of government’s neglect.

Juliana Innocent lives in Unwaba-Oju, a village in Otahe Ward of Otukpo Local Government Area of Benue State in the North-central region of Nigeria. The closest community with a primary health care centre to her village is Ogobia, which lies at the end of a 70 km unpaved road.

Road leading to Unwaba-Oju

“While going to Ogobia for antenatal care in March 2021, I had an accident that fractured my leg and hurt my back,” she narrated. Months later when Mrs Innocent delivered a boy, the baby had tremor, an abnormal rhythmic shaking in the arms, feet, hands, head and legs of newborns.

“I took the baby to hospital in Ogobia and the doctor said that he was suffering from low blood sugar. We were on admission for two weeks,” she said. But she could not keep up with the baby’s treatment schedule due to the distance of the hospital from her home. “Because of the distance and financial difficulties, I was using herbs and, unfortunately, the baby passed away eight months after delivery.”

Juliana Innocent

Mrs Innocent said most people in Unwaba-Oju use traditional herbs when they could not travel to the towns to access health care.

“Sometimes you may have money for hospital bills but you may not be able to pay for transport,” she said. Only two of her seven children were delivered in the hospital. “I had the two when Unwaba-Oju Healthcare Centre was functioning.”

Challenges of accessing healthcare in rural Benue communities

Mrs Innocent is a victim of the poor state of the primary healthcare system in Benue State. Accessing care can be a life-threatening ordeal, especially for people in the rural areas of the state where the burden of disease is disproportionately high. In some communities, pregnant women and their children travel more than 50 kilometres on motorcycles to access care. This undermines the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target 3.8, and the Nigerian government’s commitment to Universal Health Coverage (UHC), a journey towards making basic healthcare services accessible to citizens through primary healthcare centres.

In May 2024, this reporter visited four local government areas in the state to assess their PHCs. The findings are depressing.

PHC Unwaba-Oju, Otahe Ward, Otukpo LGA

Mrs Innocent’s community of Unwaba-Oju once had a PHC. But residents said it has been abandoned for over a decade. Most of the windows of the dilapidated three-bedroom bungalow were either smashed in or missing. The facility was covered by cobwebs, dirt and dust and had become home for cats, lizards, rats and spiders. Inside the building were abandoned medical equipment, rusted metal bed frames and dirt-covered mattresses.

Abandoned PHC Unwaba-Oju

Abandoned medical equipments

‘Help us’

“Lack of access to healthcare has affected our community, especially pregnant women and children. When there’s an emergency, we take the patient to neighbouring communities but sometimes there are no means (of transportation),” Sunday Anyebe , the community’s youth leader, told this reporter. “Our women depend on traditional birth attendants and sometimes there are complications and fatalities.”

Mr Anyebe appealed to the state government to address healthcare challenges of the community. “We are appealing to our governor, Reverend. Hyacinth Alia, to come to our aid,” he said.

“This community has been without a healthcare facility for more than 10 years. The government should pity our women and children and provide healthcare services and facilities to enhance their quality of life,” Mr Anyebe said.

Sunday Anyebe, Unwaba-Oju Youth Chairman

PHC Tse-Indyer, Logo LGA

Zugwem Udoji, a 27-year-old housewife, lost her twins during childbirth at the PHC in Tse-Indyer. She said the facility “crushed my opportunity of becoming a mother of twins.”

Mrs Udoji said she was six months pregnant when she had a miscarriage.

“I woke up that morning in February 2023 to an intense pain around my lower abdomen. When my husband took me to the clinic, there was no medicine to relieve me from the pains.”

Mrs Udoji said before the miscarriage, she was going for antenatal but was not tested or checked. “Even if you complain about something abnormal, they will either give you an injection or recommend medicine for you to go and buy,” she said.

She still believed she would not have lost her pregnancy if the PHC in Tse-Indyer was adequately equipped. “I know that a hospital is supposed to carry out tests on pregnant women but that clinic doesn’t do that. I would have been a mother to twins.”

When this reporter visited Mrs Udoji in her residence in Tse-Indyer, she was carrying a three months old baby she delivered after the loss of her twins.

Zugwem Udoji and her 3 months old baby

Death of a woman

69-year-old Isaac Toryina lives in a small village called Tse-Torazege, about two kilometres away from Tse-Indyer. The village is located in Mbavuur North-West, 16-17 kilometres from Abeda-Shitile, a major town along the Abeda-Afia road in Mbavuur Ward of Logo LGA.

On December 27, 2023, Mr Toryina lost his wife, Ngodoo, 10 days after she delivered a baby at home with the help of a traditional birth attendant. Early in the morning of 27 December, she stepped out to urinate but slumped and fell into a coma. Mr Toryina rushed her to Abeda-Shitile on a motorcycle. Unfortunately, Ngodoo was pronounced dead by the health workers on arrival in the PHC.

Road leading to Tse-Indyer

“My wife delivered at home because there’s no functional healthcare centre in this community. When she was pregnant and unwell, we went to PHC Tse-Indyer but we couldn’t get drugs there,” he said, fighting back tears. “After delivery, we went to a hospital in Abeda-Shitile and extracted mucus from the baby,”

Giving a picture of what led to his wife’s death, he said: “We went to bed that night and she was fine. Around 4 a.m. in the morning she stepped out to urinate and stayed beyond usual. I came out and found her lying unconscious. I couldn’t think of that clinic (referring to PHC Tse-Indyer) because even if we had gone there, we wouldn’t have found medicine.”

Mr Toryina said his wife might have lived if there were facilities for emergency obstetrics services in his community. “If there were a good clinic in this area, her situation would have been managed and she would have been alive.”

Mrs Toryina left behind a five-month-old-child, who is being breast fed by nursing mothers in the community. When this reporter visited Tse-Torazege, his grief and sorrow was palpable as Mr Toryina sat alone on a wooden chair at the entrance of his hut.

Isaac Toryina

PHC Tse-Indyer

From outside, PHC Tse-Indyer looked like a clinic, but the courtyard was overgrown with weeds. Inside the building there was no ceiling board and the windows were broken. There was no waiting room. Two rickety beds complete the story of neglect.

PHC Tse-Indyer hospital bed

Philip Shingir, the consulting Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW) in charge of the PHC, said it had no electricity, potable water or toilets, adding that the facility had no security guards and a staff quarters.

For child deliveries; Mr Shingir said he usually bought water for use, but during the rainy season the PHC staff use rainwater for cleaning, bathing and drinking.

“Now that there’s no water, I usually send someone to a nearby town to collect water for the PHC,” Asked what he does in cases of emergency, he said; “I have a motorcycle. I will pick one gallon. From here to Abeda is about 16-17 kilometres,I will go there and get water,” he replied.

The PHC was eerily quiet, without power supply, fan or solar lights. The empty medicine stores suggested not much was going on at the facility. No rooms designated for male and female patients. A few metres away from the delivery room are two clinical toilets which the health workers have turned into their sleeping quarters.

Clinical toilets where health workers sleep

Mr Shingir said the government only supplies antimalarial drugs to the clinic. “We can only test and treat common malaria infections here, not severe ones,” he added. “If there’s patients here, sometimes I use my personal money to buy medicine in Abeda for treatment. But we don’t accept in-patients, we prefer bed-rest because we lack capacity to do so,” Asked what happens if there was child delivery at night, he said “We can use local light or a handset that has light.”

“We only have one bed in the maternity section. “If there are two women delivering at the same time we will look for a mat. The woman that is closer to deliver will stay on the delivery bed while the other one will sleep on the mat.”

Delivery Room, PHC Tse-Indyer

Is the government aware?

“Yes. The government does come for supervision and we equally give reports on the status of the health centre,” Mr Shingir responded to the question.

The signage at PHC Tse-Indyer indicated that the centre was built by Logo Local Government Council and commissioned on February 12, 2012 by George Akume, the governor of the state at the time.

PHC Tse-Indyer Entrance View

PHC Awulema, Ohimini LGA

Mercy Inalegwu, a mother of two, reflected on the past when newborns were checked for jaundice before leaving PHC Awulema. She said lack of equipment at the centre to check their bilirubin levels led to the death of three of her children.

Mercy Inalegwu

“The first children were twins in 2005, a boy and a girl. I delivered at home because this hospital (referring to PHC Awulema) had nobody there. The girl passed at birth but the boy lived for four days and passed away,” Mrs Inalegwu recalled sorrowfully.

She hadn’t known that newborns are supposed to be checked for jaundice before leaving a birth centre, until her sister told her.

“When I lost my first two children, I explained what happened to my sister who stays in Port Harcourt and she told me it was jaundice. In 2009, I had twins again – both boys. One died immediately, I then followed my sister’s instructions by placing the living boy in the sun every morning and he survived,” she said.

“If there is a healthcare centre here in Awulema and there are health workers inside working, I wouldn’t have lost my children because it was just a similar case of jaundice. I am sure they would have noticed it,” she said.

In Awulema, Ohimini LGA, accessing quality healthcare service at home is a mirage. The inhabitants travel to Otukpo to seek care or use herbs at home.

Road leading to Awulema

The PHC Awulema is in Oglewu Ehaje ward, along the Otukpo-Enugu road. The desolate facility is evidence of the serious deterioration in public health services in Benue State. The facility is collapsing with its untended garden growing wild.

PHC Awulema long view

The only signs of life within the PHC at the time this reporter visited were the sounds of mice scuttling and scavenging for what had been left in the building.

PHC Awulema side view

Clement Okwubi, the head of Awulema village, has lived in the village for over 40 years. He said residents depend on herbs due to poor health care services in the community. “When one is sick, there are herbs that we use for treatment – when it is above us, we rush the person to Otukpo.”

The retired agricultural officer said poor health care service in his community had caused his people suffering, deaths and loss of function. “Those who cannot afford to seek medical care in Otukpo are giving up on life,” he said.

PHC Awulema back view

Due to the deplorable state of the PHC, the health workers have been relocated to an abandoned hospital project of the federal government in the community. But when this reporter visited the place, no one was seen at the facility. Asked about their whereabouts, Barack, not his real name, said: “They hardly come to work and even when they come they don’t stay long.”

PHC, Tse-Kpum, Vandeikya LGA

When this reporter visited Vandeikya in May, it was hard for him to locate PHC Tse-Kpum, as the facility is sandwiched between houses, along the Adikpo Vandeikya express road. One has to pass through people’s compounds to access the centre. The first thing you notice is that the walls of the old decrepit buildings are crumbling.

The facility is two mud blocks of buildings that were probably constructed in the 1960s, and is one of the oldest buildings in the community. The facility has no laboratory, toilets or water facility. Patients and health providers use the pit latrines of the neighbouring houses when pressed by nature.

PHC Tse-Kpum

Wilfred Goja, a member of the Village Development Committee for the health centre, described the embarrassment patients face due to lack of toilets in the facility.

“Once someone comes to this clinic, it’s assumed the person is infected and some people wouldn’t allow their toilet facility to be used.” Asked what they do in such a situation, Mr Goja said: “they go into nearby bushes for convenience.”

Mark Ikpa is the Chairman of the Village Development Committee of PHC Tse-Kpum. Mr Ikpa said: “People rarely come to this clinic because there is a lack of resources. The healthcare providers do not have accommodation, water sanitations and hygiene. They seek permission from the surrounding houses to use their latrines.”

Inside the PHC Tse-Kpum

He urged the government to address the needs of workers and the community. “Government should help build this facility and provide more staff to provide access to quality healthcare services,” said Ikpa.

The PHC is located in Mbagbera Council Ward of Vandeikya LGA. In May when this reporter visited the centre, his first sight was a rusted zinc on two mud blocks sitting on 50 square metres of land. In the wards, there were two beds. One of the beds had worn-out mattresses while the other had nothing. The centre does not have a cleaner and no health workers were seen within the facility.

PHC Tse-Kpum patients ward view

PHCs in Nigeria

According to National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), a PHC in Nigeria should span a minimum land area of 1,200 square metres, have two rooms with cross ventilation, functional doors, and netted windows, along with separate male and female toilet facilities supplied with water. The facility should also have a motorised borehole for clean water, power supply, a sanitary waste collection point, a waste disposal site, clear signage visible from entry and exit points, fencing with gate and generator houses, and staff accommodation consisting of two units of one-bedroom self-contained apartments.

‘I don’t talk to the press’ – ES, Benue Healthcare Board

The Benue State government, on July 16, 2016 under the Samuel Ortom administration, published that it paid N1.2 billion counterpart funding to access N2.4 billion for construction and equipment of “Modern Primary Health Centres” across the state. Investigations, however, have revealed that most of the PHCs in the state lack the capacity to provide basic essential healthcare services. They are generally plagued by inadequate equipment, poor infrastructure, lack of essential drug supply, poor staffing, and have no capacity to provide basic emergency obstetrics services.

Health ministry and Human Services keep mute

The reporter then sent a Freedom of Information (FOI) request to the state’s ministry of health on the conditions of its PHCs and on how much of the N2.4 billion had been released, the works done and other budgetary releases from 2016-2023.

The reporter visited the ministry several times requesting to see the commissioner, Yanmar Ortese. On 6 June, when he was in the office, Fidelis Igbang, his secretary, denied the reporter access to the commissioner.

The FOI request, despite being acknowledged to have been received, was not responded to as of the time of filing this report.

When contacted for this report, Grace Wende, the Executive Secretary, Benue State Primary Healthcare Board, became hostile to the reporter after he asked for an explanation for the poor condition of PHCs in the state. The Public official snapped: “I don’t talk to the press. I cannot answer you. Go and meet the Commissioner for Health,” she contemptuously dismissed the reporter, all the while pressing her cellphone.

Letter submitted to health ministry

Benue’s N2.4 billion primary healthcare projects

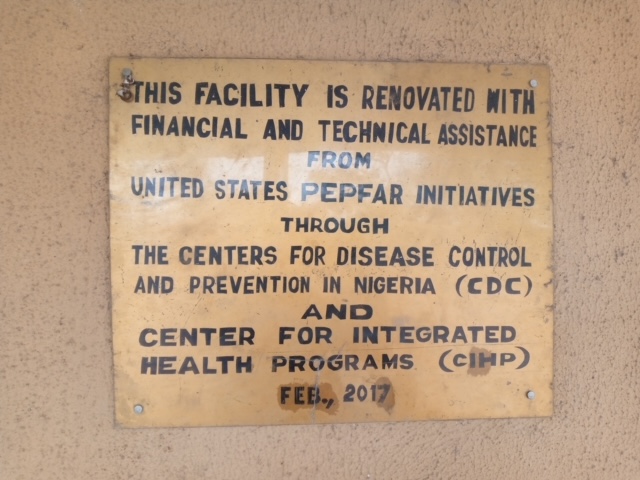

In 2017, the state government renovated selected primary healthcare facilities with financial and technical assistance from the United States PEPFAR Initiatives through the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Nigeria (CDC) and Center for Integrated Health Program (CIHP).

Sign of a renovated PHC facility

The renovation took place a year after the state government announced the payment of N1.2 billion counterpart funding to access N2.4 billion for construction and equipment of PHCs across the state. Investigation, however, revealed that none of the renovated facilities met the minimum standard for PHC in Nigeria as set by the NPHCDA. Most of the facilities are without source of clean water, functional beds, power supply, sanitary waste collection, perimeter fence, and staff accommodation.

Benue ranked low in subnational healthcare delivery

In 2023, BudgIT, a civic organisation revealed that Benue State committed only 9.67 per cent of its total spending for the period on healthcare (inclusive of capital and recurrent expenditure). In a document, titled “Subnational Healthcare Delivery for Improved Economic Development” BudgIT detailed that at 63.5 per cent, immunisation coverage for children aged 12 to 23 months in the state is the 14th lowest among the 36 States.

“One out of every 56 children born in Benue die within their first 28 days of life. In a similar fashion, 42 in every 1,000 live births do not live long enough to celebrate their fifth birthday,” the documents reveal.

The report recommends that the state provides equity funding for National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), a gateway of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) and regularise primary health facility bank accounts in all wards to enable access to the BHCPF.

This story was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID).