INVESTIGATION: Benue govt’s poor investment in primary healthcare worsens maternal and child mortality

Benue State in Nigeria’s north-central region has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in Nigeria. And this is due to the widespread lack of access to healthcare across its rural communities. In this report, ARINZE CHIJIOKE visits Gboko and Ohimini Local Government Areas (LGAs), exposing the tragic stories of maternal and child mortality and highlighting the state government’s neglect of healthcare needs.

An ancient structure that bears no semblance to a healthcare centre sits at the middle of Affoh, one of the communities nestled in the remotest part of Gboko local government area (LGA) in Benue State.

Built in 1986 through community contributions, the facility has three rooms: one for deliveries, another serving as both a waiting area and patients’ sleeping quarters, and a third, added in 2018, housing a cold room, was also funded by individual contributions.

In 2023, Laadi Terhemba, eight months pregnant, was rushed to this facility after she began bleeding and needed a blood transfusion. Outside the facility, blood donors were on ground, waiting to be called upon to help save her life. But the workers said that they could not attend to her because they lacked essential equipment such as infusion pumps, blood warmers, rapid infusers, and pressure devices necessary for blood transfusions.

Akaayaa Msugh, Terhemba’s relative, recounted that they were referred to Gboko General Hospital, 30 kilometers away from the community. This journey, fuelled by a desperate hope for a miracle, became a death march. Terhemba died on the way with her unborn child after losing a lot of blood.

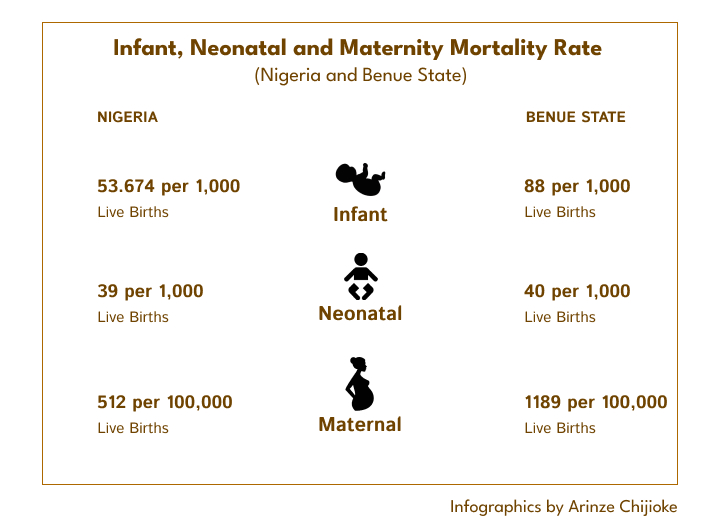

This is not an isolated incident. Benue State, situated in north-central Nigeria, had a maternal mortality rate of 1,189 per 100,000 live births as of 2020. These figures are nowhere near the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target of 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

Toilet facility, delivery table, bed and store room Inside Affoh primary health centre

Toilet facility, delivery table, bed and store room Inside Affoh primary health centre

Nigeria accounts for the second highest number of maternal and child deaths globally, contributing 12 percent of the world’s total. According to UNICEF global maternal mortality report, about 82,000 Nigerian women die every year due to pregnancy or childbirth complications. Findings show how dilapidated rural facilities in Gboko and Ohimini contribute to this national crisis.

“We brought her back home,” Msugh mourns, his voice heavy with grief. “We buried her. The pain is still raw, knowing this tragedy could have been avoided with a functional healthcare centre.”

That would have been Terhemba’s first child. Now, all that is left is her husband.

A helpless community

Stepping inside the so-called “healthcare centre” reveals the extent of the community’s helplessness. Three metal bed frames, one with a single rickety mattress, constitute the facility’s “bed capacity.”

Light blue material, a makeshift shield against mosquitoes and rain, hangs limply on the windows. The delivery room which has a single table where women lay during childbirth paints a picture of despair. Crumbling ceilings expose gaping holes, water stains mar the walls, with a mouldy smell and no electricity.There are also no essential supplies, hospital equipment and drugs.

“These challenges force pregnant women to travel an hour on an untarred road to Gboko main town where they can access care,” said village head of Affoh, Manungu Tyoakaa. “During dry season the road is wet and muddy and further delay travel time.”

It is a story of pain for residents of Affoh, including Teryimawho who lost her child in 2023

Tyoakaa lamented that seeking treatment at the local health centre which he helped build is as futile as staying home. While he lacked specific data, Tyoakaa noted that the community has lost many lives due to the absence of functional healthcare. He recalled a night in 2023 when a family member needed urgent medical attention and had to be taken to Gboko by motorcycle, as the local health centre was non-functional.

Akaayaa Msugh, Secretary of the Affoh Village Development Committee, added that delays in accessing medical care have resulted in severe complications for many women. Shawon Teryima lost her child in 2023 after he became ill and couldn’t get treatment in Affoh. “His skin started peeling off, and we relied on local medication, thinking he would recover,” she said. “When his condition worsened, we rushed him to Gboko, but it was too late.”

Teryima said she has lost hope in the community health centre and hardly visits the facility. She informed this newspaper that she, along with other women who can afford it, prefer to stay near Gboko, where they are confident of receiving the necessary medical care during pregnancy. She mentioned that this decision is to avoid complications that arise from traveling long hours on bad roads while seated on motorcycles.

Teryila Richard, a health worker that has worked at the PHC since 2017 lamented about the shortage of staff alongside the lack of the necessary equipment to make the facility function efficiently. He said that the centre has only three workers catering for the estimated 3000 people in the community. According to Richard, one of the three health workers is a volunteer staff.

“The lack of resources is crippling,” he continued. “We resort to measuring pregnancies with tape as there are no scanning machines here. We’re limited to basic tests, and forget about proper checkups, the facilities simply aren’t there.”

Even basic care comes with challenges. “If a treatable case arrives,” Richard says, “we often have to travel to Gboko ourselves to buy medication. Ideally, we refer patients, especially pregnant women, to Gboko General Hospital to avoid complications.”

“The sole important government contribution we have gotten so far is a cold room,” Richard sighs. “Even handling two expecting mothers at once is a struggle, and we have to assess each case individually based on their condition.”

Communities in Ohimini turn to local herbs and concoctions

Communities across Benue grapple with a similar lack of resources. Awulema, a far-flung and deprived community in Ohimini Local Government Area, serves as a prime example. The once-functional healthcare centre in the community now stands as a monument to broken promises.

Built during the administration of ex-governor, George Akume in the early 2000, the PHC brought joy to residents who had suffered for years without access to healthcare. There were midwives, nurses, and doctors.

“Men did not have to take their pregnant wives outside the community, we accessed care because health workers were always on ground,” Aweluma village head, Clement Okwubi said.

Dilapidated toile facilities, broken walls and roofs inside Aweluma PHC

But now, a sad decline has set in, with investigation revealing the facility’s abandonment for over two years. Its walls adorned with cracks and some parts supported with sticks. The ceilings have fallen off, the roofs and doors are barely hanging on, while shattered windows stare out vacantly.

The surrounding is covered with overgrown bushes. The toilet and bathroom facilities, which are supposed to serve both male and female patients, are destroyed from their foundations with no doors.

Fear, not just of a lack of supplies, also keeps health workers away. Okwubi alleged that the previous administration under Samuel Ortom stopped paying salaries, leading to an exodus of staff. Now, the abandoned structure is said to be home to snakes and other reptiles, further deterring any potential return of healthcare workers.

During pregnancy, women travel on motorcycles to Otukpo, another local government which is a 6km journey from Awulema on a bumpy road. While this might seem manageable, the cost becomes a significant hurdle. A single motorcycle ride can cost N1500, an amount many families simply cannot afford. Private hospitals which are closer charge out of pocket amounts to offer care.

This lack of accessible and affordable care resonates with a statement made by Benue’s Commissioner for Women’s Affairs, Mrs. Tabitha Igirigi, at a 2022 public function. She identified three key factors contributing to maternal and child health issues in the state. These factors include, the attitude of some healthcare providers, delays in seeking medical attention, and the burden of transport costs.

“These challenges have increased the rate at which our women depend on traditional birth attendants in the community who cannot handle some difficulties that women face during pregnancy and delivery,” said Okwubi. “They also depend on local herbs in the absence of a functional health centre.”

Budgit’s 2023 state of states report showed that as much as 17.7 per cent of women were delivered by traditional birth attendants and 17.2 per cent by a relative or a friend in Benue state. Only 59.1 per cent of women were assisted by skilled health personnel in delivering their children, with only 2.5 per cent of women were covered by health insurance.

Residents share their experience amid lack of a functional PHC in Awulema

Both Okwubi and Youth leader of Awulema, Amedu Itodo say that politicians have visited the community severally to canvass for votes, using the opportunity to promise them about reviving the PHC. But they never come back.

“We want the current administration to intervene and make our PHC functional again because we might lose our mothers and children if nothing is done,” said Okwubi.

Even children bear the brunt

In Benue, it is not just women who bear the brunt of lack of access to healthcare, even infants lose their lives. According to the 2021 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS report), one out of every 56 children born in the state die within their first 28 days of life. The national average is 34 per 1,000 live births.

Maria Peter is one out of several women who have lost their children due to the absence of healthcare. In 2014, she lost one of her children because she could not access healthcare on time when she was in labour.

“At the Aweluma PHC, there was no health worker on ground, I had to be rushed to Otukpo on a bike, the road was dilapidated, “she said. “When I got to the hospital, I waited because there were other patients that had to be attended to, the hospital did not also have enough doctors.”

Available reports show that Benue state has less than 600 doctors attending to over six million residents, with some general hospitals having only two doctors attending to thousands of patients.

“All of these resulted in complications, leading to the loss of her baby,” Peter lamented. At Otukpo, the doctors told her that it would have been different if her community had a functional PHC. Now, women in the community hardly attend ante-natal care.

“I was sad and would have been dead by now, but I am just trying to stay strong,” she said.

Among the causes of neonatal mortality, premature birth, birth complications (birth asphyxia/trauma), neonatal infections and congenital anomalies remain the leading causes of neonatal deaths.

Like Peter, Cicilia Garba had complications when she was pregnant with her fourth child. After she was rushed to the Awulema PHC, there was nobody to attend to her, she was rushed to Otukpo where she was attended to.

Onyiloko Peter paints a similar picture. While five of her seven children enjoyed smooth deliveries at Otukpo General Hospital, the remaining two deliveries were a harrowing experience. Unable to find any healthcare workers at the deserted Awulema PHC, she was forced to deliver at home, enduring excruciating pain and risking her own life.

Ushakuma Anenga, a Benue state-based Obstetrics and Gynecology specialist highlights a critical, often overlooked hurdle in seeking medical care during pregnancy in these rural communities.

He said there is the challenge of delay in deciding to access healthcare service on the part of women during pregnancies across communities in the area.

“In some of these communities, women wait for their husband before making decisions to attend ante-natal care, these men provide the transport needed to get to functional health centres,” he said.

Poor releases worsening situation

Successive governments in Benue State have not prioritised provision of healthcare to underserved communities. An analysis of the state government’s budget performance shows a culture of poor release of funds budgeted for healthcare provision.

For instance, in the 2022 budget, out of N540m budgeted for rehabilitation/ repairs of hospitals/ health centres, only N193.57m, representing 35.8 per cent was released. Out of N979m budgeted for purchase of health, medical equipment, N630m, representing 64.4 per cent was released. Also, out of N1.298bn earmarked for construction of hospitals/health centres, only N532m was released.

The sum of N17m was also budgeted in 2023 for the purchase of maternal and child health care equipment in the State but nothing was released in the first quarter. Furthermore, out of N275,437,109, meant for the purchase of health, medical equipment in the 2023 budget, N84,423,978 was released as at third quarter. Out of N74.56m, earmarked for the construction/provision of hospitals/health centres, N46.148m was released as at third quarter. Also, out of N127.34m, earmarked for the rehabilitation/repairs of hospitals/ health centres, N116.03m was released as at third quarter.

In 2024, the current administration of Governor Hyacinth Alia allocated 15 percent of the budget to the health sector, a significant leap from 9.67 per cent in 2023. However, there are concerns that releases might be a major challenge.

The novel idea that was buried

Between 2007-2015, the administration of Gabriel Suswam introduced the Bond scheme an incentive-based payment scheme that rewards clinical students of Benue origin who agree to work in underserved communities after their university studies.

Under the programme, medical students received financial support from the state government while at university and were required to serve for at least two years after graduation. According to findings, most of the health officials in the General Hospitals are a product of the arrangement.

However, the administration of Ortom cancelled the programme because it could not sustain payment of N100,000 monthly to student doctors. Health workers are leaving primary and secondary healthcare levels to tertiary level or even NGOs. Some general hospitals still have only two doctors attending to thousands of patients.

Former Nigeria Medical Association, (NMA) chairman, Samuel Otene, once described the acute shortage of medical personnel and critical medical equipment as “dire”, noting that it will ground healthcare services to a halt if urgent steps were not taken.

Road leading to the PHC, room where patients sleep and falling ceiling inside Affoh PHC

In September 2023, the Alia-led administration announced that it was reviving the scheme. But findings say that is yet to happen. Reacting, Anenga said “students have filled some data forms and the process has been included in the budget.”

“Preparations to commence the scheme is at an advanced stage, if that is done, it will help us retain our doctors because most of them leave the state upon graduation.”

Any way out?

Consultant Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Garki hospital Abuja, Dr Bimbo Akintunde, said that local communities are entitled to the same healthcare treatment given to those in cities, hence the state government must prioritise the provision of health centres that are well equipped.

“There should be no inequality,” she said. “Skilled medical personnel must be given good remuneration and incentives to motivate them to stay back in the local communities.”

On his part, Anenga, who doubles as the second vice president of the NMA adds that tackling maternal mortality in Benue will require investment in infrastructure, roads, availability and accessibility of healthcare service, personnel who have the right skills and essential drugs and empowerment of women to enable them make decisions.

He, however, said that the state government has been working to tackle the widespread lack of manpower by improving the condition of service like increasing hazard allowance that used to be N5000 to N35,000.

“At the Benue State University Teaching hospital, there is massive improvement in terms of health infrastructure”, he said. “There has also been renovation of General Hospitals, but a lot more remains to be done at the primary healthcare level.”

We have Basic Healthcare -Govt

When this reporter reached out to the Executive Secretary, Benue State Primary Healthcare Board, Wende Grace, she said that the state governor recently warned them not to talk to the press.

“The person who can respond to your questions as a journalistis is the health commissioner”, she said. “If you go and the honourable commissioner wants me to clarify, he will ask me to come to his office.”

When this reporter told her about the findings, she said “You cannot say a primary healthcare centre is not functional when we have Basic Healthcare services operating in the state.”

Efforts were made to reach Dr. Yanmar Ortese, the Commissioner for Health and Human Resources in the state, regarding the findings of this report via calls and a text message sent on June 12, 2024. He responded on Friday, June 14, after a reminder, stating only that the state government, with support from the World Bank, is actively enhancing primary healthcare delivery.

This report is produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusion and Accountability project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.